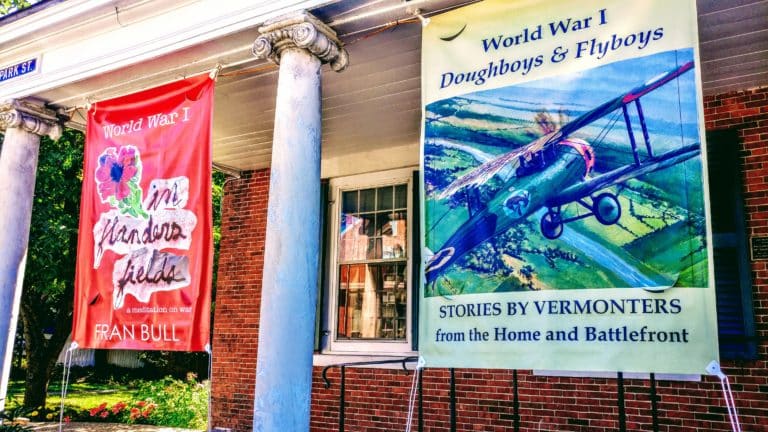

The official opening on Friday night was very excellent! The main theme is Flyboys and Doughboys, and then there's Flanders in the middle of it all, as a work of art.

Below is a very nice article from the local paper. – Fran

Posted on August 9, 2018 | By John Flowers

MIDDLEBURY — It was idealistically, perhaps even naively, dubbed “the war to end all wars” after an international accord brought an end to the carnage of World War I on Nov. 11, 1918.

But man’s inhumanity to man has continued unabated during the century that has followed that first Armistice Day. Now the Sheldon Museum of Vermont History is offering an exhibit that uses period clothing, correspondence, memorabilia, weaponry and photos donated by Addison County families to convey the drama, violence and local response to WWI through the eyes of some of the people who lived it.

“Doughboys and Flyboys: WWI Stories by Vermonters from the Home and Battlefront” debuted on July 31 and will end, symbolically, on Nov. 11. The exhibit boasts a treasure trove of fascinating historical artifacts, roughly 25 percent of them culled from the family of Sheldon Museum Director Bill Brooks. The Sheldon show includes a variety of gear, war souvenirs and family letters penned and received by Brooks’ grandfather, Dr. Jacob J. Ross of Middlebury, a local physician who served as a flight surgeon in France with the 17th Aero Squadron.

Also included are WWI letters written by two other prominent Middlebury citizens: Waldo Heinrichs, a pilot with the 95th Aero Squadron, known then as “luckiest man in the war” for surviving two plane crashes and internment in a German hospital; and Werner Neuse, a German by birth, who enlisted in the German army as a teenager shortly after his father, Richard Neuse (also a German soldier) was killed. Werner Neuse is the grandfather of longtime Middlebury attorney Karl Neuse.

Werner Neuse later immigrated to the United States, became a citizen, earned his graduate degrees and joined Middlebury College’s German Department. He helped to start the College’s German summer language school. Ironically, Neuse and Heinrichs lived on the same block of South Street in Middlebury following the war.

Ross was a physician in Middlebury and head of the physical education department of Middlebury College when the United States entered WWI in 1917. He volunteered to serve, in spite of the fact he was in his 40s and had three young children at the time.

“He didn’t have to volunteer, but he did,” Brooks said.

The Rosses would later buy a camp on Long Point in Ferrisburgh. It was there that Jacob kept his WWI-related memorabilia, according to Brooks.

“There was a barrel filled with German helmets and some of the things he wore — a sword, a bugle,” Brooks said, noting some of those items served as very realistic toys for children in the family.

But over the years, those WWI relics took on a greater significance for Brooks, an avid historian. The landmark anniversary of the end of WWI gave him the perfect excuse to package his grandfather’s wartime collection and showcase it as part of a broader Sheldon exhibit. The letters between Ross and his wife, Hannah Elizabeth Holmes Ross, sum up the tender bond and torturous separation between spouses on the home front and soldiers in war-torn Europe. That correspondence provides context for the ominous gas masks, German luger pistol, cartridge belts and other implements of destruction that bear witness to the horrific trench warfare and mustard gas attacks that claimed so many lives during the relentless conflagration.

“I can't tell you how near and dear you are to me,” Hannah writes to her husband in a letter dated Oct, 6, 1918. “I'd give worlds to put my head on your shoulder tonight.”

Hannah, in a series of messages, keeps her husband informed about goings-on around Middlebury and the state. For example, she alludes to the restrictions imposed in Middlebury by a Spanish influenza epidemic.

“This is a lousy time for the doctors, though the worst is over here in Middlebury, at least so far as the college goes,” she writes. “Colds, grip and influenza; schools, churches, movies are closed and everybody is staying at home. Prof. Robinson's mother has died. A blessed relief to her and her family. She was entirely out of her head... I wrote you Mrs. Skillings died. There have been a few deaths at college from pneumonia following influenza.”

Jacob echoes his wife’s affection in his replies, and he doesn’t mince words in describing the hell on Earth he is witnessing an ocean away.

On July 14, 1918, he wrote Hannah the following account of his travels through an unspecified community in France:

“The street was as completely blocked as if you had blown into the street the Battell block and the block opposite. We passed out of the city and came to the battlefield where the Hun had made a stand. I saw a sight never to be forgotten. British and Hun dead were still on the field.”

Approximately 116,500 U.S. soldiers died during WWI, a four-year conflict that resulted in a combined total of 18 million military/civilian deaths.

According to statistics compiled by Vermont’s Adjutant General, approximately 16,000 Vermont men served in the military during WWI. Of those, 629 were killed in action or died in service, and 778 were wounded in action. Addison County sent 781 of its own into the war. Forty-one of those local soldiers were killed in action or died in service, and 43 were wounded, according to state figures.

Descendants of those soldiers, along with WWI memorabilia buffs, gladly loaned material for the exhibit, according to Brooks.

“The response has been extraordinary and surprising,” he said.

Visitors can see vintage photos of local soldiers posing proudly in their military regalia. While the soldiers are long gone, their uniforms of some remain and are part of the exhibit. The late Stephen Freeman trained American WWI pilots stateside before they were unleashed over the skies of France, Belgium and Germany. Freeman, interviewed multiple times by this scribe, passed away on July 10, 1999, at the age of 101. His uniform currently stands at attention at the Sheldon.

Colorful period posters (pictured, right) urge citizens to volunteer for military service or to financially support the war effort.

“Beat back the Hun with Liberty Bonds,” reads one poster, punctuating the point through its depiction of a shadowy, grimacing German soldier creeping through a bombed-out landscape, blood dripping from his bayonet.

“If you want to fight, join the Marines,” reads another poster, which uses the image of a fetching young woman as a recruiting inducement.

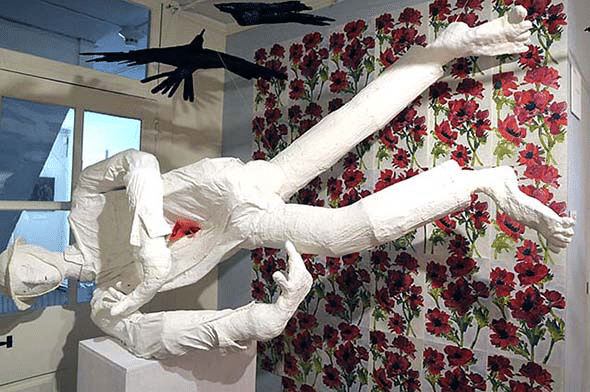

The focal point of the exhibit is a dramatic art installation created by internationally renowned artist Fran Bull of Brandon. She’s dubbed it “In Flanders Field,” after the famous poem by Lt. Col. John McCrae — a medical officer with the Canadian Army who had taught pathology at the University of Vermont’s Medical School prior to the war. He penned it in 1915 after the Second Battle of Ypres in the Flanders region of Belgium.

In his poem, McCrae notes the irony of how quickly the beautiful red poppies grow on the graves of the many fallen soldiers.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

Bull conjures that same irony through her art installation, a combination of sculpture and ivory white fabric evoking a battlefield in Belgium sullied with the grim sounds and sights of war.

“I re-imagined the poem as a work of visual art,” Bull explained. “Sky with singing birds; fields of red poppies and white crosses; the lamentations of corpses — these were my points of departure.”

The larks depicted in Bull’s artwork become bomber planes, while crosses and coffins morph into formal grids. Flowers and blood-red rags stand for lost treasures and remembrance.

Her installation includes white sculptures of the mythical Lysistrarta and her female friends, who promise only to grant their husbands physical intimacy when they abandon war — a concept inspired by the work of fifth-century Greek playwright Aristophanes.

Another sculpture depicts a pilot falling helplessly from his damaged plane.

Bull hopes her artwork can add to the debate against warfare and violence.

“There has to be another solution,” she said.

Bull has invited visitors to gently tuck into her art installation messages on crimson paper that sum up their feelings about the exhibit and war in general.

“The heart breaks, and breaks again,” reads one.

“War is hell,” reads another. “The human race fails to learn the lessons of history.”

Reporter John Flowers is at johnf@addisonindependent.com.